Social ostracism has been present since the time of ancient Greeks, but its modern English synonym is a rather new addition to the dictionary. In today’s world, the meaning of Boycott is not something that needs to be explained to most people living in the 21st century. However, in the 19th century, the situation was very different as the person behind this ignoble eponym was not yet a part of history and the meaning of boycott, was not yet found in the dictionary.

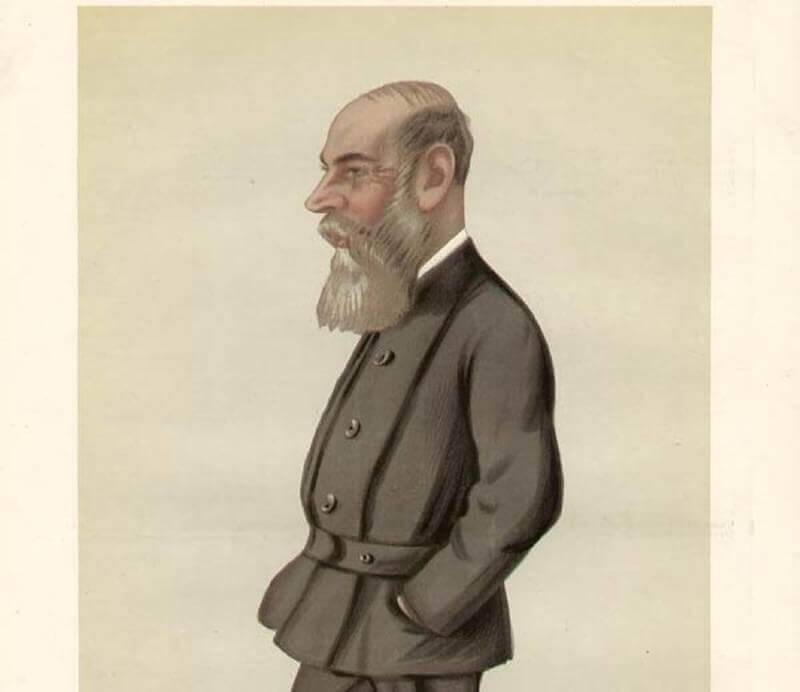

The meaning of Boycott is a rather new addition to the English dictionary and for this, we have only one man to thank, who became one of the most hated persons of his time & that is Charles Cunningham Boycott. A man with French ancestry, who was English by birth & spent most notable period of his life in Ireland, Charles Boycott’s name would have been missing from history & English lexicon, hadn’t he been living on a rapidly changing scenario of a time and place, where history decided to pause and change direction and give the world a new set of values, to live with.

Charles Cunningham Boycott was born on 12th March 1832 in the village of Burgh St Peter in Norfolk England. Charles Boycott’s original family surname had been “Boycatt”, and his baptism records show his name as Charles Boycatt. His parents – Reverend Boycatt & his wife were Huguenots – a religious group of French protestants, whose ancestors had fled France in 1685 fearing religious persecution. However, the family had lived in Norfolk for almost a century and a half and were English for all practical purposes.

Charles Boycatt became Charles Boycott when his parents changed his name in the year 1841. After preliminary education in a boarding school in London, he joined the Royal Military Academy in 1848 at Woolwich in southeast London. Unfortunately, the next year he was discharged from the academy after failing a periodic exam. However, his family came to his rescue when they helped him in the purchase of officer commissions in the British Army, in 1850.

Charles Boycott arrived in Ireland as part of his official duties in the regiment, soon after his joining the services. Even when his ill health forced him to sell his commission in 1853, he decided to remain in Ireland.

Retired from his job in the British army, Charles Cunningham Boycott searched for job avenues elsewhere. As a man has to work, if he wants money to survive. He began as a small landlord in County Tipperary of Ireland. However, later after acquiring an inheritance, Charles Boycott moved to Achill Island situated on the western coast of Ireland. Here 2000 acres of land (belonging to Irish Church Mission Society) was sublet to him by his friend Murray McGregor Blacker, a local magistrate.

However, trouble soon started for Charles Cunningham Boycott, in Achill island when he developed misunderstandings with the local population. He was accused of assaulting a local person – Thomas Clarke, over a petty financial dispute. Although this matter was sorted out when Clarke, withdrew his complaints, this would be a signal of more bad things to come in the future.

Charles Boycott would also get in personal & legal battle against the agent from whom McGregor Blacker had leased the lands of Achill Church Mission Estate – Mr. Carr. The reason for this difference again rose from supporting different candidates in the local political scenario & clash of other financial interests. Their dispute finally ended up in the court, where Carr had to pay Charles Cunningham Boycott 500 pounds in damages.

In spite of facing a long struggle against adverse circumstances (in Boycott’s own words), he finally became financially prosperous. However, in 1871 after staying for 17 years in Achill Island, Charles Boycott started to search for better prospects in the mainland, where he could be closer to the denser human settlement. His friend Murray McGregor Blacker had migrated to the United States, and spending the rest of his life on an island, cut off by the sea, no longer appealed to him.

An opportunity soon presented to Charles Cunningham Boycott, when John Crichton, the 3rd earl of Erne, a wealthy landowner invited Charles Boycott and offered him an opportunity to manage his lands. The earl owned 40,386 acres of land in different parts of Ireland. Charles Boycott soon became an agent for the earl, managing his lands and the property in the County Mayo. In 1873 Boycott moved to Lough Mask House, 6 kilometers from the town of Ballinrobe in County Mayo.

As we have said earlier that meaning of Boycott had not yet existed in the English dictionary till then. However, events that would soon occur in the new habitat of Charles Cunningham Boycott, would soon make the meaning of Boycott, known to people not just in England or Ireland, but all over the world.

When Charles Boycott, took Lough Mask House on lease for a period of 31 years, he must have thought of spending the remainder of his life in this rather peaceful place, as his present abode and position was much better than what he had earlier in Achill island. As a representative of the earl, his job was to collect rents from the tenant farmers living in the earl’s land. Retaining 10% of the collection as his payment, gave him a handsome amount of 500 pounds a year, which was considered as a good amount of money during that period.

However, his expected peaceful life would not remain so, for a very long period. Serving for more than 20 years as a caretaker landlord in Achill Island had made Boycott a hard taskmaster, who could be very harsh on the workers when the situation so demanded. Besides collecting rents from other tenant farmers, Boycott also employed many laborers, stable boys, coachmen for driving horse-drawn carts and servants. Lack of cooperation from all these would later contribute to his downfall.

For the earl, however, Charles Boycott was the best man for the job. The title of Captain, bestowed by other smaller tenants on Boycott for his past official actions & temperament was what the Earl of Erne wanted in an able English administrator and he totally believed that Captain Charles Boycott was the right person to manage his property. Here it would once again be prudent to reiterate that Captain Charles Boycott was certainly no “Captain” and this addition to his name was purely an affectation.

In the late 1870s, Ireland was facing some serious political turmoil, due to hardships faced by many people in the country. The entire land of the country was owned by just 0.2% of the population, who roughly were just 10,000 people. Most of these were small landlords & half of the land in the country was owned by just 750 individuals. Most of these large landlords mostly lived far away from their own property, and had agents like Charles Cunningham Boycott, to manage their estates in their absence.

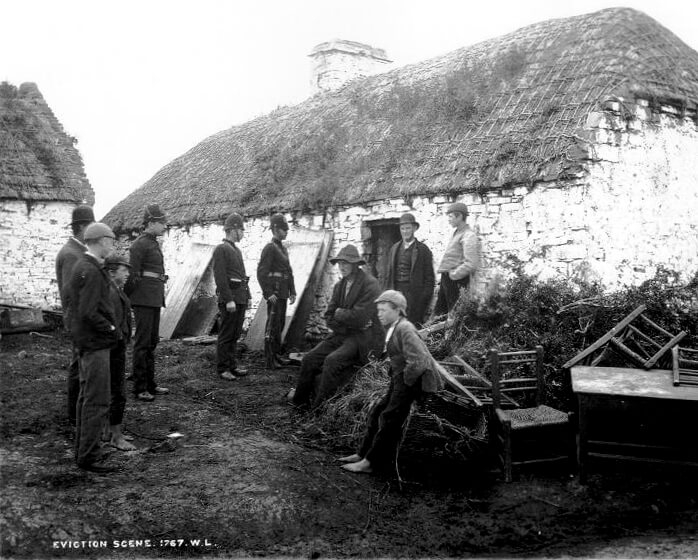

The estates of these landlords were divided into few large and many small farms, which were rented to tenant farmers. These tenant farmers had no legal hold of over these properties & they could be evicted even if they paid the rents expected of them, in time. There were many small farmers who worked on the larger farms and finally there were landless laborers who worked on farms of the others.

The poor tenant farmers were very often exploited by the landlords and their supervising agents. Raising rents beyond the ability of these hapless people & mass forceful evictions were very common. There was also a constant threat of famine. However, as is the law of nature every action is met with an equal and opposite reaction & the same followed here too.

The farmers formed a big percentage of the total population and their living conditions & position in the society could easily influence the political environment of the country. By the 1850s, the farmer of the nation had already begun to form an association and demanded – fair rent, the fixity of tenure & free sale. By the 1870s different nationalistic organizations were supporting the grievances of tenant farmers and this would soon affect the political atmosphere of County Mayo.

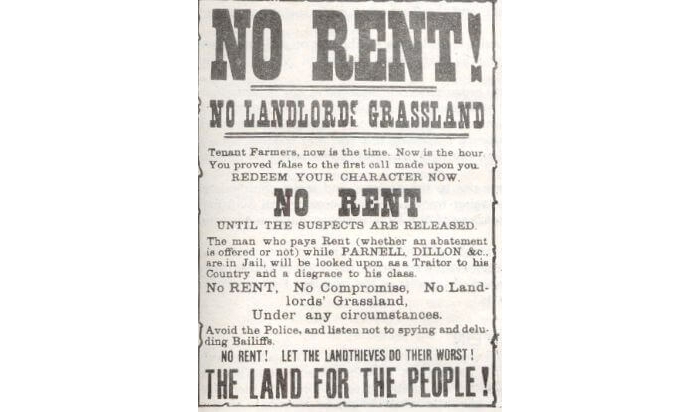

In the 1870s the whole of Ireland saw the beginning of the Irish Land War, the civil unrest movement that would last till the 1890s. The movement led by Irish National Land League was mostly non-violent, but some occasional incidences of violence and death were also reported. However, the main goal of this movement was to resist the landowner’s totalitarian efforts to control the life & property of tenant farmers, by evicting them from their property, even when they were struggling to pay the rent.

The movement to resist police from forcefully removing tenants & compel the landlords to reduce the rents would reach County Mayo too. However, forceful conflict with armed police was certainly not on the agenda of the people, who were just fighting to get their basic human rights. Here social ostracization of certain members representing the landowners would come into play, which totally would redefine the meaning of Boycott.

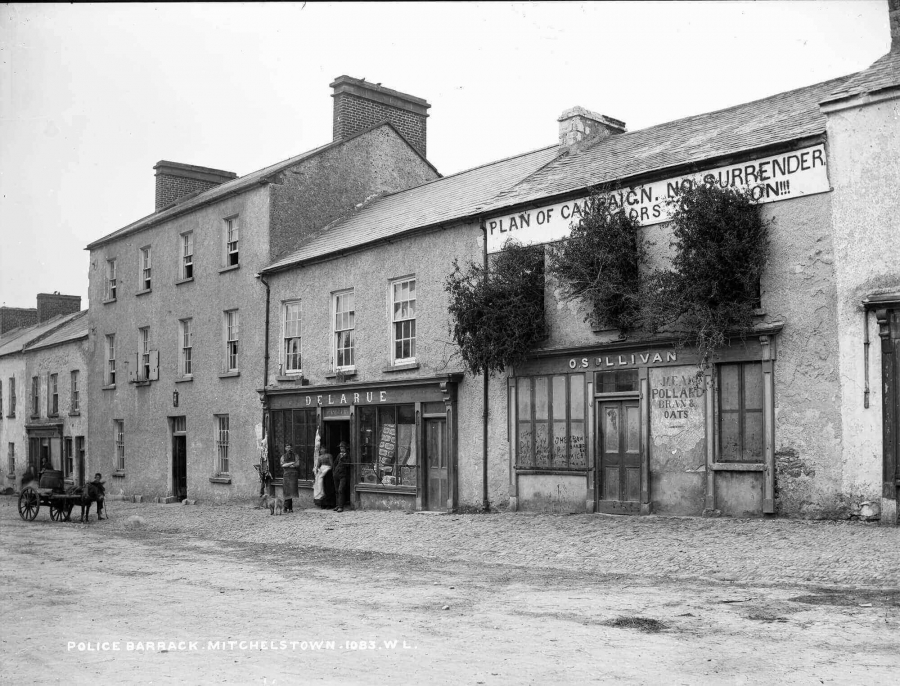

Soon the events that followed in Lough Mask would take Charles Boycott in a path of infamy forever. The resistance movement was very active in the Lough Mask area, where Father John O’Malley had been an active local leader opposing the landlords. He had also initiated a laborer’s strike in the area in August 1880. For Boycott, the troubles began in its most severe form in September 1880.

The confrontation started when Lord Erne asked his tenants for the payments, a job which was entrusted to Charles Boycott. However, the tenants had asked for a 25% reduction of the rents, whereas the Earl agreed to only a 10% reduction. A confrontation was unavoidable between the two sides. Obviously, it was the Earl who was responsible for the decision, however, it would be Charles Cunningham Boycott who would face the consequences, in the absence of the real landlord.

The showdown began when eviction notices were sent to 11 tenants, by Charles Boycott. The locals had enough of Boycott and the bullying methods of the landlords in general. The women of the area began throwing stones, mud & manure on the person serving eviction notices & accompanying police personals. These hapless people were forced to flee from the scene, to avoid further embarrassment. However, this was just the beginning of bad luck for Boycott, as the coming days would go on to prove.

The members of the Irish Land League (Mayo branch) soon came to the support of the disillusioned tenants & they urged all the people employed by Boycott to leave their jobs & leave Charles Boycott helpless and totally isolated in the local community. The shopkeepers were advised to refuse to serve him and laborers were instructed to not offer Boycott their services.

Charles Boycott soon found himself in dire straits, when he found that nobody would help him in his household work or in his professional duties. Neither he had any people to help him with his – poultry, sheep, cattle and horses; nor he had men to tend to his crops, which were ready for harvest.

Charles Cunningham Boycott even found it difficult to purchase food from the local market. However, it was the next desperate decision taken by him, that would make the meaning of Boycott, well known to people all over the world.

Charles Boycott left without any option was running out of patience & ideas. In his desperation, he thought that if the news of his misfortune reached the English, they would certainly come to his help. Although this would work out to a certain advantage of Boycott, it also had a fallout, which Boycott may not have expected. It would take the little-known tragic story of Boycott outside of County Mayo & make it world-famous news of the time, giving a new meaning of Boycott to the world.

On 14th October of 1880, Charles Cunningham Boycott sent a letter to the famous newspaper – “The Times” describing in detail his predicament and other hardships that he was facing. The letter described in detail about – how people sent by him to deliver an eviction notice to the tenant farmers were hounded by them.

The letter also described how the Land League had forced all employees of Boycott to leave their job and he had no workmen, laborers or stablemen to help him in his farm or his house. Even people entrusted (by him) to deliver mail to and from the post office were threatened & stopped from doing their job. Things had come to such a pass, that even shopkeepers were not supplying him basic supplies. His walls had been destroyed & lock was broken down and crops were being stolen & destroyed by outsiders. He ended the letter by mentioning that even his life was in danger.

Soon after the letter was published another reporter (Bernard Becker) from “Daily News” traveled to Ireland to see things for himself. He corroborated the problems described by Charles Boycott. He further mentioned that Charles Cunningham Boycott had 500 pounds worth of crops, that needed to be harvested urgently, or in absence of the required manpower, it would rot.

The reports sent by Bernard Becker were once again published in “Belfast News-Letter” and “Daily Express”. The news about misery faced by Boycott was no longer restricted to County Mayo, but by now the whole world knew the meaning of Boycott.

An Englishman was in trouble in Ireland, where he was facing a boycott by the local members of society, backed by a political organization. As this news reverberated around Europe (and perhaps the entire world) support for Boycott started to pour in.

On 29th October 1880, the Dublin Daily Express proposed setting up a fund to save Boycott’s crops. The plan was to send a team of men to County Mayo, who would also use force for self-defense if the situation so arose. A Boycott relief expedition was established by November 1880, to fund the armed expedition to Lough Mask to save Boycott and his crops. A decent sum of 2000 pounds was raised by – Daily Express, Daily News and Daily Telegraph and soon the fund found support from many different sectors.

The idea of an influx of armed outsiders was viewed by many nationalists as an invasion. Opposition to the arrival of armed soldiers was expressed from many different sections of society. Boycott himself insisted that a large number of armed men were not required, as he feared that this could spark off unnecessary violence. Hence, he requested that only a small group of laborers, sufficient enough to do the job was desired.

In spite of all the controversy, 50 men finally were sent for harvesting the crops. To guard & protect them a regiment of the 19th Royal Hussars (a cavalry regiment of British Army), & more than 1000 men of Royal Irish Constabulary had to be deployed. Although the Boycott expedition faced many hostile protests while passing through County Mayo, however, there was no real violent incidence. Perhaps this was the only bright streak in the whole unpleasant scenario, where at least 10,000 pounds were spent to harvest crops worth 500 pounds.

Charles Boycott himself realized that his time in Lough Mask House was over & it was time for him to leave the place for good. On 27th November 1880, Charles Cunningham Boycott and his family finally left Lough Mask House under protection from the 19th Hussars. The boycott of Charles Boycott was seen even as they left when no driver could be found for driving the carriage that had been hired for the family. An army ambulance was finally used to transport them to the Claremorris railway station, from where the family boarded a train for Dublin.

However, Charles Boycott’s infamy had spread far and wide by now. The hotel in Dublin where Charles Boycott had taken up accommodation, received threats that it would be boycotted if Charles Boycott was allowed to stay there. Finally, Captain Charles Boycott, who had planned to stay in Dublin for a week was forced to leave the hotel in haste & he left Ireland in disgrace on 1st December 1880, for England.

Even when Boycott visited the US to meet their friends in the spring of 1881, he registered his name & that of his wife as – Mr. and Mrs. Charles Cunningham. Although the media of the United States, highlighted the trip of Captain Charles Boycott; the couple themselves tried their best to keep a very low profile. However, this was of little success as the meaning of word boycott was now known to everyone.

In August 1881, Captain Charles Boycott once again returned to Lough Mask House in Ireland, to evaluate the situation. However, he soon realized that the ground realities now were very different and he could never return or settle back here. In 1886 Boycott finally sold his property.

In 1886 Charles Cunningham Boycott again took up the job as the land agent for Hugh Adair's estate in Suffolk, England and moved into the accommodation allotted for the agent in Flixton. Here he continued to carry out his duties sincerely, soon earning the reputation of having an understanding but firm nature.

Charles Cunningham Boycott finally died on 19 June 1897, aged 65 years in his home in Flixton after being ill for some time. Captain Charles Boycott's last day on the earth was also the day that Queen Victoria was celebrating her diamond jubilee, which was being celebrated with great fanfare all around the British empire. However, the only thing Charles Boycott had in his share was eternal infamy, which he may not have deserved.

It is Father John O Malley, one of the local leaders of Land League in Lough Mask area of County Mayo, who supposedly coined the term “Boycott” in September 1880. The meaning of boycott to ostracise people was used locally at the time, but with the news of Charles Boycott spreading, the use of boycott word also spread like wildfire, all around the world. It was one of the most successful nonviolent measures against the British, in Ireland of the time. Soon the people all over the world would know the meaning of boycott, a new word in the dictionary & use it in their own fight against injustice.

Charles Cunningham Boycott is long gone, but his name lives on infamy forever. But did Captain Charles Boycott really deserve all the hate & bitterness that he deserved? Certainly, the work he was doing was not setting an exemplary model of how landlords should behave. But he was just following orders from Lord Erne, with no powers to take independent decisions himself. We have to remember that it was a different time and values followed by people in their daily life were quite different from those of the modern world.

Does a man honestly doing his job, within the purview of law, for someone else; even when this directly harms others, deserves infamy for eternity, is a question that would be tough to answer, even after so many years after Charles Boycott’s soul departed the Earth.